What I learned building a non-profit

Last year, I co-founded a non-profit. Here’s a few things I learned.

First, some context

In March of 2020, I started Helping Hands Community with my brother and two former Uber executives.

Our goal was to help people vulnerable to COVID-19: the elderly and immunocompromised. The pandemic made it dangerous for them to leave home, so we built a platform to connect them with local volunteers that could deliver groceries and supplies.

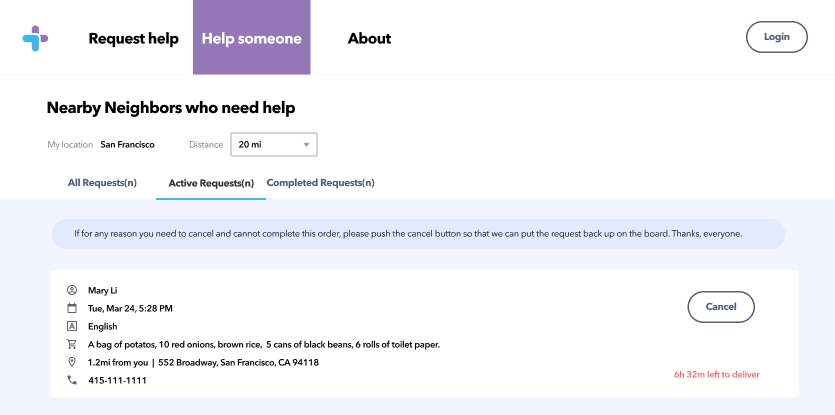

The site started as a simple two-sided marketplace: requesters could enter what they needed on a form, and volunteers could sign up to fulfill requests. We’d present local requests on a dashboard, and our site would automatically facilitate volunteer assignment and deliveries.

Over time, the product moved away from a two-sided marketplace and towards a hub-and-spoke model: Helping Hands now partners with large organizations (such as food banks or churches) and provides software tools + a large volunteer fleet to enable mass delivery of supplies.

(The above is a video, click to view it!)

(The above is a video, click to view it!)

As of today, Helping Hands has facilitated roughly 550,000 supply deliveries across 48 US states.

For posterity, here’s a rough timeline:

- Mid-March: My brother and I found ourselves anxiously watching as the pandemic hit. Restless for something to do, we met several folks interested in building this site with us.

- March 15 - April 1st: Our team sprinted to quickly build a prototype of the initial website (two-sided marketplace). We were sprinting hard - lots of sleepless nights! At the end of it, we launched a pseudo-pilot in the Bay Area. A few dozen deliveries trickled in over this time.

- Month of April: We found team members who were based in Chicago, New York, and Austin, and tried to gain adoption there. We also found lots of volunteers to join us - by the end of the month, we had roughly fifty. (More on that later). By the end of the month, we’d completed roughly a few hundred deliveries - good, but nothing near what we initially envisioned.

- Month of May: This is where we started exploring partnerships: We built an Uber integration as well as tools to enable what we called “Community Delivery” - mass-delivery events conducted through our fleet of volunteers. This is where things really started to pick up; we got into thousands of deliveries, mostly enabled by mass events.

- June - present - The organization was fully going at this point, and embraced mass-delivery fully, enabling hundreds of thousands of deliveries. This is also where I began to ramp down my involvement; as I started my first full-time job at Vanta.

The early days were notable for several reasons:

- The team never met in person.

- It was purely volunteer-based; no one was paid.

- Unlike myself, the majority of team members were contributing part-time. These factors - remote, volunteer-based, and part-time - led to some interesting challenges.

Finally, before the rest of this post, I want to emphasize I was only heavily involved in the beginning - those initial few months from March through June. While my efforts helped initially get the non-profit off the ground, there are many people who have kept things going since then, and the credit rests with them. The majority of deliveries occurred after I was actively involved!

Onto the learnings.

Avoid building marketplaces from scratch, unless you really have to

The classic startup dream is to come up with an idea, code up an app in two weeks, throw it out there (maybe with a sprinkle of social media marketing), and hit viral growth. In our case, we did the first three parts… but initially, the viral growth didn’t happen.

Gaining traction can be pretty hard. It’s especially hard if you’re trying to build a two-sided marketplace - as we were attempting to do initially, by making both requestors sign up to ask for deliveries, and volunteers sign up to conduct them.

That’s because marketplaces are initially chain-link systems. Their growth is limited by the slowest part; it doesn’t matter how good the supply-side is if the demand isn’t there. We learned that the hard way with our first iteration: ironically, we had tons of volunteers signing up to help, but comparatively few people asking for it. At one point, we had fifteen times as many volunteers as requestors!

Our slow growth was because we didn’t understand our users. We were building a service for elderly folks, but didn’t know how to reach them. It sounds obvious in retrospect, but as tech people, we didn’t realize that a well-placed help line would be more accessible to the elderly than a written form, or that local Facebook groups spread awareness better than social media broadcasts.

We couldn’t reach product-market fit until we understood our users - which brings me to the second challenge of two-sided marketplaces: understanding your users is now twice as hard, because you now have two sets of users, each with their own distribution channels, needs, and behavior. Think about it: selling a product to one set of customers is hard enough! Why would you make it two unless you absolutely have to?

An alternative approach would have been to focus solely on building the supply side ourselves. That’s what we eventually did - we built only tools to recruit and coordinate volunteers. We then approached large organizations - like churches, non-profits, and food banks - and provided our large volunteer base and tools to them. Not only did these organizations already know lots of people - generating instant demand - they were also very close with their users: saving us effort on user research, discovery, and analytics.

Doing this simplified us to a “1.5-sided” marketplace, and it enabled us to grow much faster.

Pick a neutral, but memorable name

This one is pretty silly. I wish we’d spent more time thinking about the name.

Another team member had already bought the domain name helpinghands.community, so we went with that. In my opinion, that was suboptimal: Helping Hands is probably the most generic non-profit name possible. It’s super on-the-nose. We even met other non-profits doing the exact same thing - supply delivery during COVID-19 - that were named Helping Hands!

The obvious place where this hurts is SEO, but there’s also the issue of memorability. Our conversions would’ve likely been more effective if the name stuck out more.

There was also the cheese factor - each time I’d tell someone my non-profit was called “Helping Hands”, I’d cringe a little. To the point where I found myself subconsciously avoiding the name!

If I could go back, I’d advocate for a name that is neutral but memorable over one that’s emotionally packed but generic.

The press doesn’t match reality… but it isn’t that important anyways

In the early days, we tried to gain users by getting good press. We talked to several news outlets, like Forbes and Mercury News.

Across each press interview, a specific narrative emerged: A team of Silicon Valley executives envisioned a product to solve food insecurity issues, and “designed” a stellar team to pitch in. While I won’t get into specifics, that’s not fully how it went down. The initial days were much messier than that. Much of the team (myself included) wasn’t even in Silicon Valley. And we were still figuring out what exactly to build. But that’s the narrative that made newspapers most willing to write about us.

But here’s the thing: other than feeling good, it’s not even clear that the press bought us much. We didn’t see significant increases in local signups when our story aired on the local news. Other than social media buzz, we didn’t see a measurable change in output when published in the news.

It’s something I’ll keep in mind for the future: Interviews are a nice-to-have, not a critical step to get a product going. Doing good is more important than looking good; great press should follow from a great product, not the other way around.

Keep the team small until you hit product-market fit

There was a period about two weeks after launch - around mid-April - where we added about thirty volunteers to the org. The problem was, we hadn’t figured out our exact product yet.

While adding people was well-intentioned, I can’t overstate how much more chaotic things became. The number of stakeholders for a single design increased dramatically - decisions that could be resolved in a two-minute conversation now took two meetings and a set of flowcharts. Engineers started getting pings from marketing asking to tweak features that were going to be removed the next day (to be clear, not blaming marketing here - they’re doing their job!) To make matters worse, a lot of these folks (understandably) had day jobs and so could only put in a few hours a week. That’s a big problem when progress depends on alignment in schedules.

We had to take two weeks to nail down processes and a decision hierarchy - a hierarchy for an organization that didn’t even exist 4 weeks prior! And to be clear: this was all somewhat unnecessary, since we hadn’t hit the exponential growth that justified the people yet.

The problem with hiring people is it forces your organization to operate like a ship. And ships have inertia. Once you point them in a direction, it’s hard to turn - and when you haven’t hit product-market fit yet, you want to be able to turn quickly. That means keeping your team to the smallest set needed to do the experiments to find product-market fit.

Next time I hear a pre-PMF startup say “we grew 5x in headcount last year!”, I’ll default to being a little more skeptical of whether that’s a good thing.

Go all in, so that you can stay focused

This one’s more personal to me, so your mileage may vary. But during those few months, I had a few other events come up - another early project to potentially co-found, a job to start. While these only took at most a quarter of my time, they had an impact on over half of my productivity and will. It was super disproportionate. For me, I learned I can’t emphasize enough the value of having only one focus: having only one subject to ponder when showering, taking a walk, or thinking passively. Those thoughts compound.

This is the same reason that adding so many part-time volunteers was challenging for us. I’d take 5 people working 40 hours a week over 15 working 20.

That’s ultimately why I ramped down on the project in June, after starting at Vanta: I wanted to focus on that.

People are good

Lastly, and probably best: I’m way less cynical than I was when I started.

In the early days, we spent so much time worrying that volunteers wouldn’t bother to sign up, or that they wouldn’t bother accepting requests, or that they’d scam those in need. None of that happened. Instead, we found thousands of delivery volunteers - each giving us useful feedback, dependable deliveries, and a genuine window into their community.

Internally, we worried we wouldn’t find anyone willing to donate their time to build the platform. That never happened either - dozens of well-meaning and talented people continue to maintain Helping Hands Community today.

Maybe it’s a COVID-19 thing - maybe folks were exceptionally generous given the circumstances. But I believe the takeaway here is more general: the vast majority of people want to do good, especially during a crisis. I’m confident we’ll see that again in the next crisis, and the one after, and the one after that. For now, I’m grateful to have seen it in this one.